By Benji Sam Mille Lacs Band Member

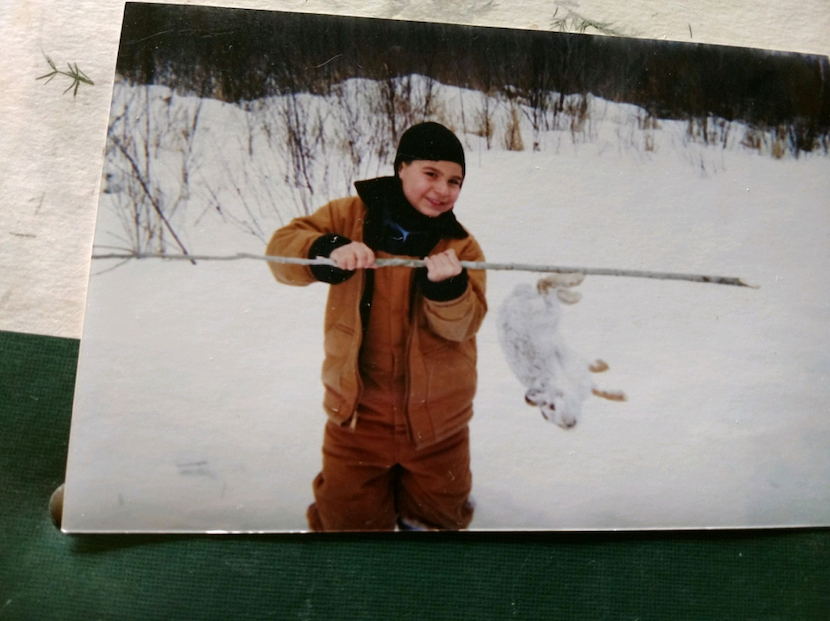

Mid- to late-winter hunting and fishing with my family provided some of my most vivid and cherished memories from my childhood. I didn't grow up with an iPad; I grew up with a shotgun, a length of wire, or a spear in my hands with snowshoes strapped to my boots. When setting snare lines for waabooz, grouse hunting, or spearing on Mille Lacs Lake, our snowshoes were as important as our very gloves and coats. These weren't just any snowshoes; these were traditional Ojibwe snowshoes built by my father, David "Amik" Sam.

Traditionally speaking, the snowshoe was debatably as important to the Anishinaabe in winter as the canoe was in summertime. The making of traditional snowshoes is a rather delicate process and can take up to a week or more to complete.

My dad would begin with an 8-foot cut of ash tree and split the log along its length to keep the wooden grains intact. This was repeated until the strips of ash measured roughly one inch squared. Each pair was customized lengthwise and measured from the ground to your shoulder for both staves. After scraping and sanding the edges, he would soak and steam the staves until they became pliable enough to bend over a snowshoe frame. "Anishinaabe snowshoes are long, narrow, and very sturdy," he would say. Each would measure roughly 12 to 14 inches in width and had an upwards toe curve to avoid snagging brush when deep in the woods.

Next, each end was carefully tacked and wrapped with rawhide to prevent separation, and after a few days of drying, the toe bar seats were carved and placed to prepare for webbing. Our relatives would use rawhide to create the webbing, which can be a difficult and daunting task when each snowshoe can utilize upwards of 80 feet of rawhide to complete. Webbing with rawhide meant a deer hide would need to be stripped of flesh and fur, brained, and dried before it was cut into thin strips for weaving. Dad always used heavy lace as it was a strong substitute for rawhide because it is faster and easier to work with. After the webbing was complete, he would apply a varnish over the entire snowshoe and place a foot wrap or rubber in the toe hole to allow for safer, easier winter travel.

My father, who just turned 69 years of age, still wears his snowshoes to this day when tasks need to be done in deep snow. And although harvesting a few fish, rabbits, or grouse here and there is no longer a life-or-death situation like it was for our ancestors, it is the tradition of independence and self-sustainability that makes us who we are as Anishinaabe. We may not be as reliant on snowshoes in winter travels like my grandfather's generation, but it is important to teach and to share knowledge with the next generation as my father did with me so that we, too, may walk on water.