Previous

2019 State of the Band Address

A Wild Ride with the GoodSky Boys

Community Efforts Delay Sandpiper Deadline

Opiate Addiction in Newborns Affecting Community

Separation of Powers Provides Checks and Balances

Youth Attend National Conference in Atlanta

Apply Now for PCs for People

Pipe and Dish is a Nay Ah Shing Tradition

Road Crews Gear Up for Winter with New Trucks

Benjamin is a Lifelong Learner – and Teacher – of Ojibwe

‘Cardio Sampler’ Gets Students’ Hearts Pumping

NON-REMOVABLE: Band Still Fighting for Reservation

Band Members Urged to Aim High

Opiate Problem Affects Everyone

Career Focused: Band Members Dedicated to Following Legal Path

Cultural Sovereignty a Major Theme at 2015 State of the Band

Legislative Counsel Stacey Thunder Unveils New Online Series

Gii Dodaiminaanig, Our Clan System

2015 State of the Band Address: Protecting the Gift

Minisinaakwaang Leadership Academy Now Offering ITV College Courses

Nay Ah Shing Staff Invited to Schoolyard Garden Conference

TERO Director Named to National Post

PCs for People Application Deadline Extended

Band Hosting Elder Abuse Awareness Conference

Commissioner Appointed to National Board

Fighting For His Culture

Hwy 169 lane closures in Vineland Feb. 9–27

Cement Mason Union Training Available

Elder's Passing Results in Controversy Over Autopsy

Rights Celebrated at Treaty Day Events

Early Education Awarded with 4-Star Parent Aware Rating

Pine Grove Proposed as NASS Satellite

Anti-Bullying Club Sends Positive Message

Fighting for our Future: Preventing and Stopping Opiate Abuse

Partners for Prevention: Helping Kids Make Healthy Choices

Band Leading Charge for New Legislation on Autopsy Objections

Chief Executive Benjamin Receives Tim Wapato Sovereign Warrior Award

Opiate Abuse Awareness Takes Spotlight

Celebrating Treaty Day 2015

Sugar Bush Season: One Sweet Tradition

Straight Talk with Joe Nayquonabe

Bella Boyd Honored at Special Olympics Minnesota Event

Mille Lacs Polar Bear Plungers Raise More Than $42,000!

Education Department Focuses on Graduation Rates

Students, Staff Celebrate Dr. Seuss’ Birthday

Low Walleye Numbers Mean Smaller Tribal Harvest

What is Self-Governance? Just Ask John

New Judge Is at Home Away From Home

24th Annual Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe Grand Celebration

Adopt-a-Shoreline Returns: Let’s Clean Up the Lake

Making the Most of the College Experience

Nay Ah Shing Graduates Looking Forward to Future

Joe Nayquonabe Named NAFOA Executive of the Year

From Government to Casinos — Living History with Doug Sam

Band Member Following Dream to Florida

Onamia Lady Panthers Chasing Hoop Dreams

9th Annual Ojibwe Language College Quiz Bowl

Chiminising Elder Shaped by Cultural Ways

Student Achievement Celebrated at American Indian Graduation Banquet

Protect Our Lands From The Sandpiper Pipeline

Band Member Has a Thirst for Knowledge

Photos from the 2015 Memorial Day Powwow

Department of Justice Proposes Legislation to Improve Access to Voting for American Indians and Alaska Natives

Forty-One Defendants Charged With Conspiracy To Traffic Drugs To Indian Reservations

From the Brainerd Dispatch

National CPR & AED Awareness Week is June 1-7

Cultural Artist Joni Boyd Teaches Youth Traditional Ways in Summer Classes

From MPR: Minnesota tribes press concerns over pipeline plan, wild rice

Anishinaabe Immersion Camp is June 23 through 25

Band Members Producing Jingle Dress Documentary

EZ Enrollment Day at Anishinaabe College

Historic Agreement Reached to Combat Crime

State Patrol looking to diversify workforce

Transportation available to Sandpiper hearing June 5

Band Hosts Tribal Relations Conference

Band Hosts Tribal Summit On Crisis of Indian Children

Minisinaakwaang speaks out against Sandpiper

Pine Grove Satellite Project Approved

ATV classes scheduled in all three districts

Eddy’s Resort: Same Name, New Look

Grand Casino Hinckley to host National Indian Gaming Commission training

Wanted: Youth powwow dancers

From the Duluth News Tribune: Mille Lacs band vows to fight Sandpiper

County rejects Social Host Ordinance

From the Star Tribune: Pipeline protest draws marchers to St. Paul

Breaking the Silence: Confronting the Problem of Elder Abuse

From the Mille Lacs Messenger: Mille Lacs Band protests pipeline

Niigaan basketball camps are June 16-18

Hinckley prepares for a Grand Celebration

From the Mille Lacs County Times: Principal Norberg begins journey into retirement

Join the 14th Annual Walk around Mille Lacs

Mark your calendar: Inaugural Gii-Ishkonigewag Powwow is July 24-26

Nay Ah Shing fifth grade graduation

Walking with Water at Nay Ah Shing

Graduate recognition ceremony is this Wednesday

Wii Du youth learn CPR

From the Brainerd Dispatch: Anishinaabe — Healing culture, healing oneself

Hwy. 169 project on schedule

Men to gather at District I immersion grounds

Nay Ah Shing Students Go To Purdue University

Band members kick off NCAI conference in St. Paul

District II community meeting features information, inspiration

132 honored for educational achievement

Election to be Held on MCT Membership Amendment

Minisinaakwaang Says No to Sandpiper

Notice of Public Meetings on Proposed Pipeline

Office Building Grand Opening in Hinckley

Indian Education Funding Gets Boost from State Lawmakers

Lawsuit Challenges Minnesota Adoption Law

Mille Lacs culture showcased in St. Paul

Benjamin sworn in for new term

Chiminising to host basketball tourneys

Grand Casino Hinckley Hosts Training Conference

Mobile Dental Clinic

Native Pride: Bill Schaaf’s Life of Service

Open house at Hinckley Medical Office Building July 23

Klapel’s Vision for DNR Based on Anishinaabe Values

Know the Rules for Dog Ownership on Tribal Lands

Moose, HHS Take Steps to Combat Opiates

DNR Installs ‘Beaver Deceiver’ in District III

Band Joins Fish and Wildlife Service to Celebrate Refuge Centennial

From NPR: White House Hosts Tribal Youth

Register Now for the 2nd Annual Family Golf Outing

DNR: State anglers closing in on walleye quota

Nay Ah Shing Students Return from GERI Residential Camp

From the Aitkin Age: CLC hires first local Ojibwe speaker/teacher

Gii-Ishkonigewag Powwow is July 24-26 in District II

From the Aitkin Age: Remembering the Sandy Lake tragedy

MIKWENDAAGOZIWAG: They are remembered

Anishinaabeg Gather to Remember Sandy Lake Tragedy

State May Shut Down Mille Lacs Walleye Harvest

Former Speaker Was a Man of Compassion

Commissioner Sworn in for Full Term

Mille Lacs Delegation Attends White House Tribal Youth Gathering

A Concrete Plan for the Future

Technology Provides Anishinaabe College Students New Options

‘If I Can Do It, Anyone Can’

Applicants sought for Ojibwe Immersion Academy Weekend Cohort

Cultural Center Hosts Fall Programs

New Principal Stresses Need for Change

Hand Drum Class Connects Boys to Heritage

The Good Way of Life at Minobimaadiziwin

Pine County Joins CodeRED Emergency Notification Service

St. Paul Declares Indigenous Peoples Day

Pipeline Opponents Make Their Case in McGregor

A Zest for Life: The Condensed Story of Dale Greene

Drumkeepers Call for One-Year Suspension of Netting

Second Pipeline Proposed for Sandpiper Corridor

49th Annual Traditional Powwow

Band Leaders Address Opiate Addiction with Elected Officials In Effort to Find Allies and Solutions

Healthy Food, Healthy People

Another Year of Doing What They Love

New Director Helps Minisinaakwaang Kick off School Year

Family and Frybread are Key Ingredients for a Successful Business

New Director Brings Unique Perspective

Community Support Services

Response Team Works to End Truancy

Vet Clinic Coming to District I

EPA Administrator Visits Mille Lacs

Highway 169 lane closures north of Milaca begin Sept. 1

Court Rules that Sandpiper Decision Was Illegal

Minnesota Indian Housing Conference, Sept. 15, 2015, Welcome Remarks by Chief Executive Melanie Benjamin

Chief Executive Addresses Housing Conference

From the Aitkin Independent Age: A Crude Awakening

Band Hosts Nibi Miinawaa Manoomin Symposium

Harvest, Poach, Jig, Winnow: Ricing Process is Tribal Tradition

History and Culture Are Alive at Rice Lake Landing

October is the Falling Leaves Moon

Band and State Leaders Continue to Build Strong Bond

Where There’s Smoke, There’s Firefighters

Wild Rice and Habitat Restoration on Lake Ogechie

Band Member named Executive Director of Minnesota Indian Affairs Council

Ground Broken for District I Housing Development

Band Departments Provide Supplies for the New School Year

Mille Lacs County Board Votes to Terminate Law Enforcement Agreement

Catholic Charities Seeks to Build Community to Work on Key Issues

Mille Lacs Band Divests from Wells Fargo

New Resource Officer Hired for Nay Ah Shing Schools

Sheriff, Police Chief Address District I Community

Ayaabadak Ishkode

Band Members Graduate from Pre-Apprenticeship Training

Band, Pine County Sign New Law Enforcement Agreement

Chiminising Hosts Ziigwan Powwow

Good People Are All Around Us

Heroin and Opioid Forum Presents Perspectives on Epidemic

HHS Employees Attend Point of Dispensing Seminar

HHS Prepares to Re-Open Four Winds

Joanne Boyd Recognized for 10 Years of Contributions to WIC Program

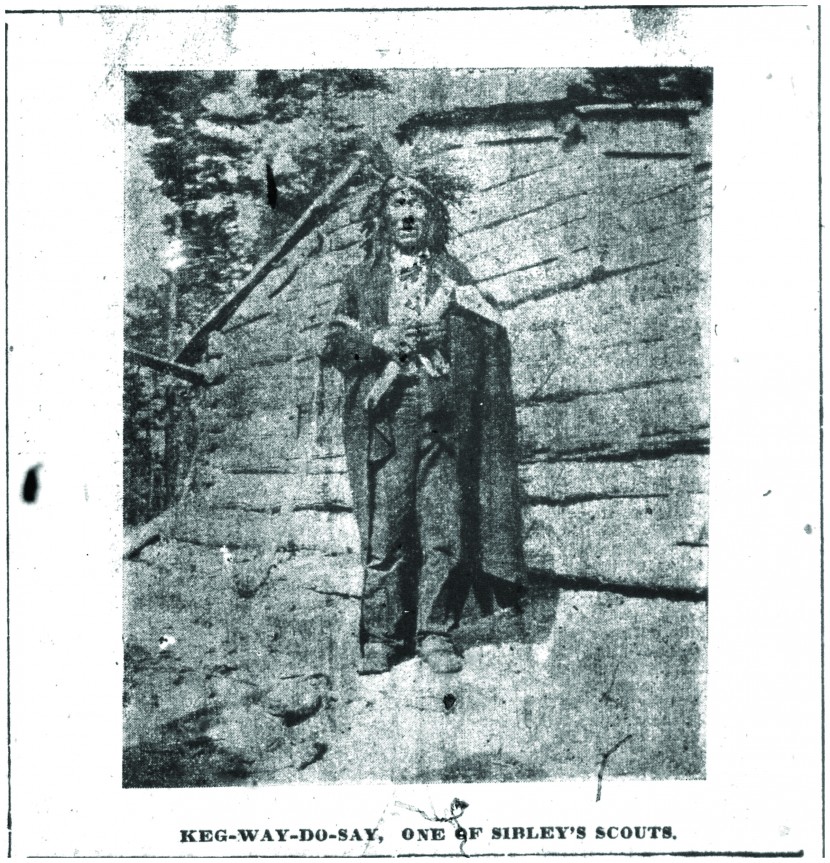

Kegg’s Message Helped Preserve Reservation

Larry ‘Amik’ Smallwood: An Anishinaabe Success Story

Leaders Meet Urban Area Band Members to Provide Updates

Native Rappers Take Stage in District I

New Hinckley Community Center is Taking Shape

Public Health Sponsors Cultural Presentation

State Seeks Public Comment on Line 3

5th Annual Adopt-a-Shoreline Clean-Up Effort on Lake Mille Lacs

Band Members and Allies State Strong Opposition to Line 3

Chameleon 5K — Rainbow of Color at Rice Lake Refuge

Commissioners Discuss Concerns with District III Band Members

District II Student Headed to Indigenous Games

Emergency Response Committee Prepares for Wildfire

Gikendandaa i’iw Ojibwemowin — Learn the Ojibwe Language

Leadership Conference Addresses Culture, Communication

Memorial Weekend Features Film, Music, Art, Powwow

Nay Ah Shing Meets Goals, Raises Bar for Next Year

Our Relationship with the Environment

Red Cross Volunteers Bring Sheltering Workshop to District I

Secretary-Treasurer Attends NCAI Conference in Connecticut

State, Federal Politics Loom Large in Indian Country

State-Tribal Relations in Action: Band Public Safety Headlines Meeting with Governor

Staying Safe, Being Prepared in Summer Months

Understanding MCT- Mille Lacs Band Issues

All We Have is Each Other

Band and Pine County Continue Collaboration on Important Issues

Commissioner Stresses Natural Resources are Gifts from Manidoo

Dentists Bring Experience, Empathy to Ne-Ia-Shing Clinic

Equine-Assisted Therapy Helps Band Members Heal, Recover

Wenji-ganawendamang Gidakiiminaan

Indigenous Games Are a Family Tradition for Reuben Gibbs

Leonard Sam Ricing and Fishing

Meetings Prepare Band Members for Constitutional Convention

Minisinaakwaang Celebrates at Gii-Ishkonigewag Powwow

Minnesota Chippewa Tribe Will Hold Constitutional Convention

New District II Associate Justice is Excited by New Role

Pipeline Risks and the Next Steps

Protecting Wisdom Keepers — Elder Abuse in Tribal Communities

Road Project Raises Concerns over Artifacts, Remains

School’s IN for Summer!

State of Minnesota Working Family Tax Credit 2017 Update

Stroke Danger Threatens MN Tribes

The 1855 Reservation: M-Opinion Says Boundaries Are Intact

Treuer Addresses Cultural Continuity, Cultural Change

What Defines Me as a Mille Lacs Band Member

Wide-Ranging Discussion at First MCT Constitutional Convention Meetings

September is National Preparedness Month

Commissioner of Administration Works to Implement Chief's Vision

Mille Lacs is Second Home for New Education Commissioner

New Health and Human Services Commissioner Sets High Goals for Healthcare in Indian Country

Camp Ripley Commander Honored at Powwow

Chief Executive Melanie Benjamin's September 2017 Letter

Comment Period Open for Changes to Wild Rice Standards

A Drum Is the Heartbeat of the Mother

Band Members Invited to Smudge Capitol

Mino Bimaadiziwin Helps Band Members Overcome Barriers

Moccasin Telegraph — The Rhythm of Ricing

September Legislative Update

Traditional Images Chosen in License Plate Contest

National Preparedness Month: Make a Plan to Help Your Neighbors and Community

Airboat Training Prepares Officers for Rescue Operations

Bassmaster Angler of the Year Tournament Returns to Mille Lacs

Love Water, Not Oil — Honor the Earth Rides for Life

Mille Lacs Corporate Ventures Names Michele Palomaki CEO of Wewinabi, Inc.

Survey Says Band Members Favor New Approach to Truancy

They Are Remembered at Big Sandy Lake

DNR Commissioner Extends Ricing Hours in District I

National Preparedness Month Week 3: Practice and Build Out Your Plans

Governor Pressures County to Sign Law Enforcement Agreement with Band

Minnesotans to Gather at State Capitol to HOLD THE LINE on Enbridge Line 3

TERC Meets with Minnesota Homeland Security and Emergency Management

Chief Executive Hosts Meet-and-Greet with New Commissioners

Legislative News — License Plates, TERO, Ethics Code

Child Support Enforcement Update October/November 2017

Newest Pipeline Developments Encouraging, But Not Resolved

Line 3 Hearings This Week in East Lake, Hinckley

New Beginnings Women's Gathering

October 2017 Message from the Chief Executive

‘Percap Patrol’ Brings Anti-Drug Message to Reservation Neighborhoods

Band Members Seek Answers, Action After Surge in Overdoses

Bassmaster Brings Anglers, Crowds Back to Mille Lacs

Community Members Step Up, Come Together to Fight Addictions

District I Welcomes Teachers and Staff of Onamia Schools

Gego Awakaanaaken Giwiiji-Bimaadiziim

It's Time for Action

Minor Trust Training Scheduled for Nov. 13

Pine Grove Students Get Hands-on Lessons in Safety

Nay Ah Shing Students Learn about Safety, Fire Prevention

Band, Pine County Work Together to Hire Community Coach

Message from the Chief Executive, November 2017

‘Percap Patrol’ Leads to Discussion, Organization, Action

Band Members, Officials Present at NCAI Convention

Let Our Voices Be Heard

Micronesian Canoes Come to Mille Lacs

November 2017 State and Local News Briefs

Circle of Health Plans Weekly MNSure Enrollment Events

Mille Lacs Chapter of Natives Against Heroin Meets

November 2017 National News Briefs

Teaching People About Anishinaabe

Band Members, Employees Chosen for Leadership Training

DAR Inducted Into Minnesota Boxing Hall of Fame

HHS Meets with U of M on Drug Courts, Precision Medicine

Walk for Family Peace Brings Awareness of Domestic Violence

Wraparound Staff Attend Homelessness Conference

Zumba Dances Its Way Into District II

Grants Department Responds to Community Needs

Immersion Teacher Receives Teaching License, Second Degree

Winter Hazard Awareness Week is Nov. 6-10

Pine County, Mille Lacs Band Seek Applicants for Community Coach Position

Mille Lacs Band Designated Heart Safe Community

Onamia Teachers Learn Ojibwemowin

Pine Grove Update — Safety, Weather, New Books

Tribal Cultural Surveys in Progress on Proposed Pipeline Corridor

Grand Casinos Honor Veterans with Free Meal

Mille Lacs Band Receives Grant to Address Opioid Crisis

Department of the Interior Searches for 17,000 Native American Individuals to Claim Accounts Before November 27 Deadline

Band to Hold Law Enforcement Rally at Capitol

Letter from Feds Confirms Boundaries, Law Enforcement Powers

Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe Files Lawsuit Against Mille Lacs County

Secretary of Interior Meets with Band, County on Law Enforcement

Band Members Rally to 'Un-Cuff Our Cops'

WEWIN Experience Inspires Youth to Take Action

Blandin Provides Lessons in Leadership and Community

Mille Lacs Band Broadband Vision, Projects Held up as Example at Statewide Conference

Annual Corporate Ventures Fall Feast

December Message from the Chief Executive

Max and His Flutes

Mediation Stalls; County Hires Attorney

Wenda-noomage-apaginigod A’aw Anishinaabe — Drug Abuse Among Anishinaabe

The Healing Power of Running

Quilting

Tribal Court Seeks Special Magistrate

Deadlines Approaching for Insurance Applications

Former Inmate Gives Back to Correctional Facility

Vet Clinic Coming to East Lake

Band Members Share Stories at Tribal Opioid Summit

Elder Refreshes Nursing Skills

Ge-Niigaanizijig Storytelling Camp

Psychologist Speaks on Race Relations, Economic Disparities

Pet Health Clinics Return to Districts I, II, and IIa

Attempted Eagle Rescue Shows Danger of Lead

Community Center is the Place to be for District I Teens

Former NHL Scout Donates to Kindergarten Class

Making Culture Cool Again

Ricing School — Learning, Fun Combine at Manoomin Harvest

Treuer Presents an Honest History of Thanksgiving

Band Members Ask Questions, Give Feedback to DNR

Ojibwe Language Becoming Priority at Onamia Schools

Pine Grove Students Study Planets, Art, Anatomy

Chippewa Tribe 2018 Election Calendar Released

LEECH LAKE BAND OF OJIBWE FILES LAWSUIT AGAINST OPIOID MANUFACTURERS

Band’s Broadband Efforts are Model at Statewide Conference

Insurance Deadline Is January 14

Message from the Chief Executive

New License Plates Available from DMV

Per Cap Patrol, Tribal Police Offer Mutual Support

Constitutional Convention Heading to Grand Portage in January

Band, Pine County Share Local Government Innovation Award

January 2018 Legislative Update

January Pine Grove Update

Mediation Continues, County Responds

County Board Approves Contracts for Legal Defense of Sheriff, Attorney

Program Fair Comes to District II

District I Health Clinic Is Taking Shape

Charlie Lippert — Engineer by Day, Language Learner by Night

DNR Program Receives Award for Fish Hatchery

Enbridge Obstacles Can’t Stop Protectors

From the Pain, to the Game

Keeping the Ojibwe Language Alive

Virgil Wind — School Board Chair Extraordinaire

Chief Executive Highlights "New Warriorism" in State of the Band Address

Executive Branch Commissioners' Reports

2018 State of the Judiciary

Police Chief Sara Rice Becomes First Tribal Chief on Minnesota POST Board

Winter Storytelling Event Focuses on Keeping Tobacco Sacred

Gaa-izhi-ina’oonwewizid A’aw Anishinaabe-abinoojiinh — What the Manidoog Gave Us as Anishinaabe to Help Our Babies

GLIFWC Officials Study Resource Management in Peru

Commissioners Attend Indigenous Governance Program

Youth Create Tribute to Mentor With Help From Native Artist, Community Members

Moccasin Telegraph — Preserving Our Language and Culture

State of the Judiciary: The ‘Ripple Effect’ of the Opioid Crisis

Band Assembly Called to Order — 2017 Legislative Highlights

February News Briefs

A New Warriorism — 2018 State of the Band Address

February Band Briefs

Power to the People — Leaders Praise Grassroots Efforts

GLIFWC Announces 2018 Summer Internships

Tribal Police Chief Earns Back-to-Back Honors

HHS Sponsors Manoomin Cookoff

East Lake Hearing Focuses on Cultural Impact of Proposed Line 3 Pipeline

Urban Youth 'Shop with a Cop'

Positive Indian Parenting Training for Trainers

Trainees Convert Centers Into Shelters

Candidates Certified for April 3 Primary Election

Igloo Project Makes Learning Fun for Wewinabi Students

Mille Lacs' Circle of Influence

New Date, Venue for Basketball Tournament

Waakobinigod A’aw Anishinaabe — That Which Pulls Anishinaabe From Their Original Teachings

Youth Powwow Returns to Chiminising March 24

BIA Forum Educates on Opioid Crisis

Polar Plunge Returns to Mille Lacs March 10

Affordable CPR/AED Class Coming to Urban Office

April 9-13 is Severe Weather Awareness Week

Pharmacist Shares the Facts on Narcan

Lady Baller — Chiminising Student Finds Success on Court

March 2018 Local News Briefs

March 2018 State and National News Briefs

DIIA Youth Bowls in State Tournament

Winter Camp Provides Hands-On Education at Rutledge

Band Member Artists Light Up the Cities

Moccasin Telegraph — Using Tobacco to Pray for Others

Four Winds Continues to Meet Band Member Needs

Know Your Government — Health and Human Services

Absentee Ballots Available for April 3 Primary

Biologists Give Update on Status of Ogaa

Treaty Rights Day Celebrates Heritage

Rachel Dorion — Harvesting Health

The Welcoming Face of Chiminising

Make Your Voice Heard: Vote!

Aadizookewin! Winter Storytellers Take Center Stage at Grand Makwa

April 3 Primary Will Narrow Field for Secretary-Treasurer, District Reps

April 2018 Message from the Chief Executive

April 2018 News Briefs

Band Seeks Self-Governance Growth Through Native Farm Bill Efforts

3rd Annual Ziigwan Youth Powwow

Native Governance Center Moderates Candidate Forums

Frances Davis — Living Through Changes in District I

Moccasin Telegraph — Springtime Sugarbushing

Band Members Elect New Secretary-Treasurer, Representative Candidates

District III Athletes Advance to State

Mille Lacs Band Announces Primary Election Results

2018 Spring Cleanup Is Coming!

Tony Buckanaga — Iron Chef Minisinaakwang

Chief Executive Marks Anniversary of Self-Governance with Senate Testimony

Ziinzibaakwadwaaboo Harvest Shows Reality of Climate Change

Prepared for Emergency

Band Members Encouraged to Apply to First Ever Tribal Youth Gathering

Bemidji Students Honored for Audio-Visual Production Work

Mille Lacs Indian Museum May Events and Classes

Beloved Wewinabi Gramma Retires

May 2018 News Briefs

District I Cleanup Rescheduled

Miigwanens Geyaabi Eni-dibaajinjigaazod — The Story of Miigwanens Continues

Moccasin Telegraph — Growing Up in Nature

50+ Program Provides Job Opportunities

The Generous Life of Beatrice Taylor

Diving into Mille Lacs Lake Biology

Language Warrior's Lifelong Love Affair with Ojibwemowin

Sugarbush — The Sweetest Tradition

Water is Who We Are — Protect Us

Minor Trust Training Rescheduled for May 16

House Members File Protest Against Rep. Sondra Erickson

Band Seeks Dismissal of Counterclaim

Band to Receive 5,000 Drug Disposal Kits to Safely Dispose of Prescriptions

Chief Executive Melanie Benjamin Accepts Orville Freeman Award

Big Weekend Ahead at Mille Lacs Indian Museum

Self-Governance Conference Recognizes Band's Historic Contributions

NAS takes 1st, 2nd at Annual Quiz Bowl

Students Learn Money Management from Experts at Minor Trust Training Seminar

May 2018 News Briefs

Weweni Inaabaji' Aw Asemaa League

All-Native Tourney Brings High-Energy Hoops to Mille Lacs

Fishery Committee Discusses Relationship with Tribes

Governor Vetoes Rice Bill

Lady Luck Estates Project Wins Award

HHS Department, U of M Seek to Reduce Disparities in Tobacco-Related Illness

June 2018 Message from the Chief Executive

Will the Real Wild Wild Rice Please Stand Up?

A Beautiful Day for a Powwow

'Gigsy' Brings Digital Media Training to Nay Ah Shing

Band Members Honored at Graduation Event

Elder Financial Exploitation on the Rise

The Family Violence Prevention Program Is Here to Help

Band Members Create Welcoming Environment at Four Winds

Moccasin Telegraph — The Center of the Moon

Namebinikaa! Nay Ah Shing Students Learn Spearing Tradition

Baabiitaw's Bush Foundation Fellowship: Year One

Gikendandaa i'iw Ojibwemowin — Learn the Ojibwe Language

Election Day is June 12

MILLE LACS BAND ANNOUNCES GENERAL ELECTION RESULTS

iQuits Project Presents Final Report

Band Supports Fond du Lac in Opposing PolyMet Land Swap

Heavy Haul of Trash at Adopt-a-Shoreline

Pomp and Pride at NAS Graduation

Hundreds of Pounds of Electronic Waste Recycled Through DNR Program

Community Activism Brings Awareness and Response to Foster Care Crisis

Wewinabi Students Receive Head Start Diplomas

State and Local News Briefs

Anishinaabe Values Motorcycle Ride Gears Up July 28

Grassroots Group Hosts Picnic

Keeping Tobacco Sacred is Theme of Digital Storytelling Interviews

Mark your calendar: Minnesota primaries are August 14!

Moccasin Telegraph — Summer Gathering

Outgoing Assembly Marks Accomplishments from Last Year

Anderson Shares Recipes for Success with Band Youth

July 2018 Message from the Chief Executive

Active in the Language

Former Tribal Judge Richard Osburn Running for Mille Lacs County Attorney

Opioid/Heroin Awareness Community Outreach

Vets Remember the Fallen at Normandy

ALICE Prepares Schools for Emergency

End-of-School-Year Picnic Brings Urban Members Together

Gikendandaa I’iw Ojibwemowin— Learn the Ojibwe Language

GLIFWC Healing Circle Run

National Veterans Exhibit Comes to Mille Lacs Indian Museum

Painting Unveiled Featuring Mille Lacs Band Marine Veteran

Mille Lacs Band Swears In New Band Assembly Members

Teen Pregnancy Program Completes Live It! Curriculum Implementation

Nay Ah Shing Summer School Has Something for Everyone

Baby Moccasin Class for Young Mothers

ClearWay Tribal Tobacco Grant Ends

BIA Agent Discusses Opioid Epidemic

State Approves Line 3; Opponents Regroup and Plan for the Next Phase

August Events at Mille Lacs Indian Museum

August News Briefs

First Homes Finished at Lady Luck Estates

August 2018 Message from the Chief Executive

Native Votes Needed in Crucial Primary

New Secretary-Treasurer Sets Agenda for Band Assembly

Band Participates in Healing Circle Run

Moccasin Telegraph — Fall Ricing

Native Americans Are Important Partners in Prevention

Cheyanne Peet — A Warrior Fighting an Invisible Enemy

Grassroots Groups Are Changing Minds and Changing Lives

Chief Executive Encourages Band Members to Vote August 14

Band Conducts First Telemetry Study of Mille Lacs Walleye

Mille Lacs Band endorses Keith Ellison for Attorney General

Brawn, Brains, Beauty, and Determination

Minzel Brings Her Message to District I Community Picnic

Osburn's First Priority: Fix the Band/County Relationship

Peggy Flanagan Hopes to Make History as Lieutenant Governor

Voting in Minnesota: Frequently Asked Questions

What's on My Primary Election Ballot?

Band Hosts Weekend Woodland Conference August 25 and 26

Mille Lacs Soil and Water Conservation District Board Announces Vacancy

New CEO visits Indian Museum

Child Seats, CPR/AED, First Aid, Smoke Alarms Available

Youth Firearms Safety Class

Coming Home/Facing Re-Entry Two-Day Workshop

Moccasin Telegraph — Sharing Traditions with Children and Grandchildren

Attention Turns to General Election

Band Partners with Neighbors, Law Enforcement at National Night Out

GLIFWC Holds Annual Mikwendaagoziwag Ceremony

September 2018 Message from the Chief Executive

Branches Meet in Spirit of Collaboration

DNR Fisheries Biologist Provides Update on Harvest, Telemetry Study, Hatchery

Get to Know Your Legislative Office Staff Members

September 2018 News Briefs

Stories from the 2018 WEWIN Conference

Youth Gathering Inspires Future Leaders

Early Education Department Prepares for School Year

It's a Public Affair

Youth Learn Leadership at Day Camp

Motorcyle Ride Brings Awareness of Anishinaabe Values

Nay Ah Shing's Gifted and Talented Program Brings Students to Purdue

Aquaculture Biologist Brings New Skills to Mille Lacs DNR

Ethnobotanist Shares Knowledge of Wild Food and Medicine

Growing Business Puts Family First

Police Seek Information after Tragic Death

Sheriff Releases Photo of Vehicle of Interest

Minor Trust Training Scheduled for October 17

Band, County Approve Law Enforcement Agreement

District II Receives Updates on Education, Circle of Health

Early Voting Underway; Plan to Vote November 6 or Sooner!

District III Residents Discuss Opioids, Education, Smudge Walk

Get to Know Your Legislative Staff

Pine Grove Plans for Year-Round School

Legislative Branch Plans Revisor's Office

Federal Judge Dismisses Mille Lacs County's Counterclaim

Family Hopes Benji's Death Leads to Justice, Healing, Unity

2018 Message from the Chief Executive

Community Members Come Together for Smudge Walk Following Homicide

Meshakwad Center Makes Fitness Fun

Adrienne Benjamin Selected to NCAIED 40 Under 40

Abinoojiiyag Curriculum Picks up STEAM

Band, GLIFWC Biologists Meet with State Advisory Committee

Band Hosts Self-Governance Conference in St. Paul

Camp Brings Spotlight to Homelessness

Family Atmosphere Promotes Learning at Minisinaakwaang

Immersion Program Builds on First Year's Success

Moccasin Telegraph — Respecting the Creator's Creation

Nurturing Nature — Curt Kalk Shares Cultural Knowledge

Pine Grove Students Go to Safety School

Gigitigemin Anishinaabewiyang

HHS Building, Community Center on Schedule in District I

Health and Human Services Hosts Annual District Health Fairs

Radinovich Hopes to Win Nolan's Seat

Sober Squad Brings Message of Healing, Hope, and Sobriety to Brainerd

Tim Walz and Peggy Flanagan: Your Team for Indian Country

St. John Reflects on First Four Months

Annual Walk to End Domestic Violence

Band Assembly Meets in Urban Area

Band Reaches Out to Mille Lacs Friends

DNR Involves Nay Ah Shing Students in Fishery Research

Early Education Students Crunch Their Way to Healthier Eating

Emy Minzel Seeks to Oust Erickson

Moccasin Telegraph — As Long As We Hear Those Drums

November 6 Is an Important Day Locally, Regionally, Nationally

November 2018 Message from the Chief Executive

November 2018 News Briefs

Ricing Is Always Worthwhile for Alicia

Secretary-Treasurer Reports on First 100 Days in Office

Democratic Candidates Rally on the Reservation

Steve Premo Becomes a Full-Time Artist

Band Member Wordsmith Gives Reading in Minneapolis

Historic Election for Native Americans

Native Thrive Looks to Empower Youth Through Sports

Urban Area Pays Tribute to Herb Sam

Benjamin Named to List of Influential Young Native Americans

Freddy's Passion for Makazinataagewin Spans Generations

Wiidanokiindiwag Youth Program Helps Out at Homeless Camp

DNR Hosts Presentation on the Real History of Thanksgiving

Minnesota Indian Education Conference Comes to Hinckley

Artwork Unveiled at Four Winds

NAS Student Project Earns Thumbs Up from Chief Executive

Chief Executive Appointed to Walz- Flanagan Transition Team

Government Center Name Changed to Honor Chief Executive Marge Anderson

Government Officials Welcome Students

December 2018 Message from the Chief Executive

Moccasin Telegraph — Coming Home

Vet Clinic Makes District I Pets Happy and Healthy

December News Briefs

Circle of Health Deadlines

GRA Director Provides 'Health Check' to Band Assembly

Who's Dallas? A Who, That's Who!

Sober Squad Members Gather for Training in District I

Band Members and Employees Attend Adverse Childhood Experiences Training

Urban Members Celebrate at Holiday Party

Generations Basketball Camp Brings Healthy Fun to District I

Thomas X Entertains, Enlightens, Inspires in District I

Upward Bound Helps Students Thrive in College and Beyond

A Christmas Wish and a Letter from Heaven

Using Art to Celebrate Diversity

Welcome Babies!

A Time Gone By

Band Members Attend Chamber Dinner

Community Development Hosts Public Meetings in January

Director of Department of Athletic Regulation Provides Update to Assembly

Anishinaabe Ice Fishing!

Counselor Knows Both Sides of Treatment Experience

Curtain Rises on Meshakwad Center

Judges Seek Input on Court System

Moccasin Telegraph — Winter Legends Start with Snowfall

January 2019 News Briefs

Band Hosts Multijurisdictional Training

Band, Pine County, East Central Public Schools Recognized for Cooperation

Lifelong Learner Is Ready to Help Others

Personal and Professional Growth Go Hand-in-Hand

'New Warriors,' Tribal Government Partner for Progress in Fight Against Opioids

Delegates Attend Constitutional Convention

District I Members Learn about Medication-Assisted Recovery, WEWIN at Community Meeting

February 2019 Moccasin Telegraph

February 2019 News Briefs

Long Road Back to School

2019 State of the Judicial Branch

2019 State of the Legislative Branch

Kayana Bearheart Joins the Guard

Special Election in District III February 5

'It Takes a Community to Heal a Community'

Artistic Curation of Cultural Traditions

Filmmaker, Hip Hop Artist Thomas X Coming to Hinckley

Summer Language Immersion Academy Applications Open

Winter Stories and Special Feast Fill Up Guests at Museum

Youth Embrace Biboon at Mille Lacs Indian Museum

DNR Announces Youth Color Drawing Contest

Neighbors Help Neighbors During Power Outage

Brandon Works for Success — On and Off the Court

Minnesota Chippewa Tribe Releases Wild Rice Report

Band Members Give Powerful Testimony At Opioid Hearing

Band Youth Spar with the Pros at Meshakwad

Department of Athletic Regulation brings world championship to casino

Moccasin Telegraph — Traditional Ojibwe Crafts

Get Ready for 2019 Tribal Harvest on Mille Lacs

Rarick Victory Means Another Special Election

Sovereignty Day Offers Hope for Better Future

Dad Doubles as Basketball Coach

What is Circle of Health?

March 2019 Message from the Chief Executive

Small Acts, Big Impacts

Verdict Came as a Surprise — To Some, that is

Housing Board Meets Members Where they Live

A Place to Call Your Own

Robin Eagle — The Friendly Face of Nay Ah Shing

Hot Cotton and Hissing Irons —Remembering Noni

Band Officials Attend MAST Impact Week

Office of Solicitor General Receives Patriot Award

Onamia Hosts Annual Concurrence Hearing

Chief Executive Announces Warriorism Grants

Prairie Island Prepares

Stronghearts Native Helpline Expands Hours

Band celebrates 20th Anniversary of treaty rights victory!

DNR Treaty Rights Cell Phone Photo Contest Winners!

Legislative Branch considers update to Revenue Allocation Plan

What is Purchased and Referred Care?

Mille Lacs Band Flag Flies at Family Justice Centers

Moccasin Telegraph — The Migration Story

April 2019 Message from the Chief Executive

Crafting Series Concludes with Celebration

New HHS Commissioner is ready to serve

One Year Out, Census Participation Encouraged

Sharing Culture Through Arts and Education

Zaagibagaang Uses Facebook, Web to Educate Tribal Members on MCT Constitution

Misi-Zaaga'iganing Basketball Tourney Promotes Year-Round Fitness

Natalie Weyaus — Working Through the Changes

Ziibaaska'Iganagooday Jingle Dress Exhibit opens

The Transformative Power of Anishinaabemowin

April 8-12 is Severe Weather Awareness Week

I Want to Be Like Rick — The Importance of Role Models

'Big Rig Vinny' — A Drive for Change

District I Rep Shares Band Assembly Update

Get Ready for Spring Cleanup!

Governor Walz Signs Historic Executive Order to Expand Tribal-State Relations

District IIa Learns about Medical Research

Lt. Gov. joins Tribal Collaborative Meeting

Chiminising Youth Bowlers Compete at Districts

You're Invited to the Minnesota Senior Games!

Education Commissioner Ratified

A Sisterhood of Lifelong Learners

Band Assembly Seeks Input on Proposed Amendments to Statutes

Decolonize Your Diet with Indigenous Foods

May 2019 Message from the Chief Executive

EIGHT CHARGED IN DRUG TRAFFICKING CONSPIRACY

Understand the Band's Lawsuit

Friends gather for Sober Night Memoriam

Supreme Court Decision Cements Treaty rights

Constitutional Convention Delegates Continue Discussion, Seek Input From Band Members

Time to talk — Equity Event Addresses Educational Disparities

New Solicitor Sworn In

A Healthy Adventure

Minisinaakwaang Celebrates Molly's Graduation

Moccasin Telegraph: Summer Traditions

A Healing Group for Chiminising

Bailey and Taylor Woommavovah: Twin Stars on St. Cloud Tech Softball Team

Community Members Work to Promote Mental Health, prevent suicide

Ethnobotanist Offers Services to Band Members

FOX 9 Series features Mille Lacs Band Members

Jingle Dress Centennial Celebrated at Indian Museum

June 2019 - Message from the Chief Executive

Music Festival

Nay Ah Shing Teams Shine at Quiz Bowl

Soldiers benefit from Cell Phone recycling

Working Together To Protect Our Waters

Track Star Runs in State Tournament

Smudge Walks Bring Neighbors Together in DIII

Grants Awarded to New Warriors

Health Advisory: Spike in Drug Overdoses

Ziibaaska'iganagooday Heard 'Round the World

Gii-Ishkonigewag Powwow Royalty Contest

She Is Not Invisible — Raising Awareness of Missing and Murdered Women

Pine County Campus Recognizes Anishinaabe Heritage

Tribal Consultation Agreement Signed

Wisdom Steps Conference Promotes Elder Health

Brownfields Program Receives Input from EPA

Supportive Housing Planned for District I

'We're the First Farmers of This Land'

Progress, Not Perfection

End-of-School-Year Picnic Celebrates Community, Achievements

Moccasin Telegraph — Old-Style Cooking

Adopt-a-Shoreline Takes Out the Trash

No Summer Vacation for Basketball Brothers

Anishinaabe Values Ride for Recovery is July 6

Graduates to Be Celebrated at Luncheon

Healing Circle Run is July 13-20

Mending Broken Hearts Training

Urban Site Manager Finds Her Passion

Wewinabi Inc. Offers Jobs, Special Discounts to Band Members

Possible World Record Muskie Boated and Released by Mille Lacs Band DNR

Mille Lacs Children Participate in Nature Walk, Cucumber Crunch

2019 Creative Native Call for Art

Why Housing Matters

Delegates Receive Training in MCT Constitution

Meet Your District III Constitutional Convention Delegates

Commissioners Receive Census Update

A Fish Story with Endless Possibilities

Cultural Role Models

Family Spirit Home Visits Help Growing Families

Siblings Launch Podcast

Pine County Wins Juvenile Justice Award

Ninham Named Interim Nay Ah Shing Principal

Breaking the Cycle

Making His Mark in Music, TV

August 2019 Message from the Chief Executive

A Royal Year for Powwow Princess

Applicants Wanted for Crime Victim Needs Assessment Community Advisory Group

Immersion Academy Weekend Cohort Seeks Applicants

MENTOR ARTIST FELLOWSHIP OPEN CALL

Urban Office, District I Host National Night Out

District III Members Receive Updates

Hands-Free Cellphone Law Is Now in Effect

DNR, Government Affairs Host Telemetry Open House

Mille Lacs Corporate Ventures Associates 'Unleash the Power Within'

Mille Lacs Band Women Bring Energy to WEWIN

Dispatches from the Mille Lacs Powwow

Advocates Available for Elders, Families

Corporate Ventures Interns Complete Summer Experience

Constitutional Convention Survey Results

Representative Blake Attends Housing Conference

Commissioner Brings Commitment to Culture

Oppression — A Band Elder Reflects

Heart-Mending, Life-Changing

Partnership Seeks Better Cancer Outcomes for American Indians through Research

September 2019 Legislative Briefs

September 2019 Message from the Chief Executive

Project Mezinichigejig Helps Band Youth Find Their Voice, Discover Talents

Jingle Dress Symposium — Inspired by History

Lakeside Stories — Original Theater by Local Youth

Miigwech, Monica

Mille Lacs Band members invited to Changemaker Retreat November 19-21

Ikwe Oganawendaan Nibi Miinawaa Manoomin

District I Meeting — Niigaan, Wiidoo, Wraparound Updates

Attorney Bound for Afghanistan with Reserves

Former Director Returns to Public Health

GLIFWC Offers HACCP Certification Course

More Than Just Fair-Weather Friends

TERO Director Wants to Help Band Members Succeed

Convention Delegates Address District III

Spirit Foods — Ethnobotanist Brings Band Members Back to Their Roots

Commissioner to Serve on MMIW Task Force

Meet Your District IIa Convention Delegates

Revisor's Office Takes Shape with New Addition

Understanding ACEs Helps Band Members Break the Cycle of Trauma

October 2019 Message from the Chief

'We Are Water' Exhibit Takes a Look at Minnesota's Way of Life

Legislative Hosts 3-Branch Meeting

Band Employees Attend NAFOA Conference

Vaping Illness Outbreak Update

Indigenous Peoples' Day Event Draws Large Crowd

Mille Lacs Recognized as Official Scenic Byway

Can You Dig It? Earthworks Does!

There Is No Honor in Racism

November 2019 Message from the Chief Executive

Remembering Leonard Sam

Niiyawen'enh

2020 Census Update — Be Sure to Check the Box

It Is Always a Choice

Self-care and Leadership Discussed at Women's Gathering

Mending Broken Hearts — The Trauma Stops Here

Hip-Hop and Politics

The 'Other' Legislature — Band Assembly Members, Staff Visit Capitol

A Family of Warriors

Healthy Pets, Healthy Community

Heroin Dealer Sentenced in Federal Court

Shaping the Future with a Complete Count

Actors Needed for Ojibwe Language-Learning Videos

Adopt-a-School Program Helps Students Succeed

Honored for Giving Back

ICWA — It Takes A Community to Keep Kids at Home

December 2019 Message from the Chief Executive

Johnny's Pheasant — A New Book by Band Member Cheryl Minnema

Making Her Own Way at B.A.T. Entertainment

Drum and Dance — Healthy Fun in District II

Band Assembly Proposes Open Meetings and Data Privacy Statute

Book Project Features Stories by Elders

New Attorney Brings Indian Country Experience

Artist Shares Jingle Dress Tradition at Central Lakes College

'I'm Thrilled to Be Back' — Mel Towle Sworn In As Commissioner of Finance

Community Learns Harmful Effects of Vaping

Would-Be Actors 'Break a Leg' at Rosetta Stone Auditions

Telemetry Research Includes Odoonibinh

Ojibwe Language Books, Rosetta Stone Will Contribute to Healthy Communities

Minnesota Chippewa Tribe 2020 Election Calendar

EPA Helps with Fuel Tank Clean-up in District I

The Constitution and Tribal Sovereignty — Let's Learn Together

Lost Boys and Broken Toys

Kids Count! Shape Children's Future in Census

Our Mississippi, Our Future

Coach Mom

Forever In Grey

Chief Attends White House Signing of MMIW Executive Order

January 2020 Message from the Chief Executive

Walking on Water

Model Student, Athlete, Leader

Why Write Stories?

Election Board Positions Open in All Districts, Urban Area

Filing Period Begins January 14 for Minnesota Chippewa Tribe Elections

Be Good Ancestors, Fight the Battles You Must, says Chief Executive Benjamin

Scholarships Available for Full-time Ojibwe Language Students

2020 State of the Judical Branch

Nayquonabe Named Assistant Commissioner of Administration

New Face in Urban Office — Billie Berry

Work, Sacrifice, and Gratitude — 2020 State of the Legislative Branch

Commissioner of Natural Resources Is New State DNR Liaison

Drum and Dance — Unity in Our Community

Questions and Answers about Census 2020

Ribbon Skirt Class

GLIFWC Announces Summer Internships

Band Member Wins Children's Literature Award

Absentee Ballots Now Available for March 31 Primary Election

MCT Student Handbook

Band Member Update on COVID-19

Early Education Program Closed Until Further Notice

State of Emergency Declared; Emergency Response Plan Activated

GRAND CASINO ANNOUNCES TEMPORARY CLOSURE OF MILLE LACS AND HINCKLEY CASINOS

Tribal Government Reduces Staffing Levels

Tribal Government Reduces Staff to Protect Communities

HUD Provides List of Low-Cost Devices, Learning Content, and Free or Low-Cost Internet Service

COVID-19 Information

StrongHearts Native Helpline Continues to Offer Services

Mille Lacs Band Issues Stay At Home Order

Stay at Home order issued by Chief Executive Melanie Benjamin

April 2020 Message from the Chief Executive

Health Officials Confirm First Case of Coronavirus COVID-19 in Mille Lacs County

Walleye Harvesters on Mille Lacs Encouraged to Use Landing Declaration Form

COVID-19 Cases Confirmed in Region

Little Spirits and Pandemic

May 2020 Message from the Chief Executive

Response Committee Remains Vigilant in COVID-19 Prevention

A Strong and Resilient People

DNR assists with bog cleanup in Onamia

Grand Casinos Issue Safety Plan

Health Services Remain Available

Health and Human Services Department readies for move

Schools Make Adjustments, Plans for Summer and Fall

Telehealth Takes Off During Pandemic

STAY-HOME ORDER STILL IN PLACE

Commissioner's Order Requires Masks on Band Property

COVID-19 Reaches Band Communities

BAND, MAYO CLINIC PARTNER FOR TESTS

Band-wide COVID-19 testing begins June 2

GRAND CASINO ANNOUNCES REOPENING DATE

Primary Election is June 9 — Absentee Voting Encouraged

Band Members Protect Native Buildings in Minneapolis

COVID-19 Testing Kicks Off in District II

Aanjibimaadizing offers education and training opportunities

A Statement from Mille Lacs Corporate Ventures on the murder of George Floyd

2020 Tribal Election Guide

Primary Narrows Field for Chief Executive, District I Representative

Bradley Harrington Files for Mille Lacs County Commissioner

IMAGEN PROGRAM SEEKS TO EMPOWER BAND MEMBER GIRLS

Weekly news summary, June 8-12

Mental Health Program Offers Help in Times of Crisis

Ge-niigaanizijig director stresses mentorship, transitions

From high school dropout to master's degree

IllumiNative, Sundance Institute and The Black List Collaborate For Inaugural Indigenous Screenwriting List

Absentee Voting Encouraged for General Election

Band Assembly establishes protocol for drafting legislation

Band Was Prepared for Pandemic — Thanks to the TERC

CARES funds finally reach tribes

Help slow the spread of COVID-19

Police chief participated in working group on use of deadly force

Weekly News Summary, June 20-26

Atlantic Coast, Dakota Access, Keystone XL: Three major defeats for Big Oil. Is Line 3 next?

U.S. Senator Tina Smith Says Congress Must Address the Crisis of COVID-19 in Tribal Communities

NCAI: Historic win for Muscogee Nation

Band member cares for community through work

Minnesota Indian Affairs Council Seeks Immediate Action from University of Minnesota

Representative seeks volunteers for child protection subcommittee

Mille Lacs Corporate Ventures Announces Promotions

Charter Associates (and Sisters) Bid a Grand Farewell

DNR to Host Manoomin Meeting August 5

Scholarship Program Now Processing Funding for Fall 2020

DII, DIII Convenience Stores Reopen in August

Reflections from a 2020 High School Graduate

Mille Lacs Corporate Ventures Obtains 8(a) Certification

Band Assembly reviews proposed legislation to create Leasing of Trust Lands Code

How to vote absentee in state and tribal elections

Smith faces challengers in August 11 state primary

Band Assembly Reviews Proposed Amendments to Titles 12 and 21

Manoomin Meeting Draws Big Crowd

Secretary/Treasurer Seeks Candidates for GRA Board

Band Assembly Weekly Update: Band Assembly Weekly Update, August 3-7, 2020

Early Ed Releases Preparedness Plan in Preparation for Phase 1

SCOTUS Affirms Reservation — Upholds Jurisdiction to Protect Native Women

Report Informs Band Members of Government Action During Pandemic

Wind, Benjamin prevail in general election

Wind, Clitso-Garcia running for Onamia School Board

Aanjibimaadizing is local administrator of COVID-19 Housing Assistance Program

Mask Order Extended Through November 30

Monolingual Ojibwemowin Books Are Now Available

Band Member's Artwork Featured in Minneapolis

Commissioner's Mask Order Extended

'HAWK' CROSSWALK WILL ENHANCE SAFETY IN DISTRICT I

September 2020 Message from the Chief Executive

Census Deadline Is Coming Soon

Wraparound Moves to Aanjibimaadizing

A Busy Month for Band Assembly

Casinos Announce New Positions for Band Members

District III Holds Community Meeting at Casino

DMV Closed September 8-11

School Year Begins with Major Changes

Frequently Asked Deer Harvest Questions

Swearing-In Ceremony for Chief Executive, District Representative Is September 8

Chief Executive, District I Representative Sworn In

Band Assembly Establishes Agenda and Live-Streaming Procedures

Virgil Wind Takes Office as District I Representative

Stronghearts Scales to Respond to Crisis within a Crisis

Virgil Wind, Becky Clitso-Garcia Running for Onamia School Board

Community Meeting Provides Update on Urban Housing Project

Manoomin Presentation September 26-27

Early Ed Seeks Members of Policy Council

Band Provides Antibody Tests

Band Receives Entrepreneurship Grant

Band Assembly Weekly Update for September 21-25, 2020

Becky Clitso-Garcia — Asking for Your Support on November 3

Secretary-Treasurer's Midterm Update

Elders Can Experience Domestic Violence

October 2020 Message from the Chief Executive

Tragedy Remembered in Online Ceremony

Band Assembly Weekly Update: Week of September 28-October 2, 2020

Meet the New Providers at Ne-Ia-Shing Clinics

Students Crunch Together for Farm-to-School

Successful Partnership Leads to Successful Students

Weekly News Summary, October 4-10

Taking a Stand by Taking a Knee

Investments

Band Assembly Weekly Update, October 5-9

The Unsung Hero of the Legislative Branch

Election Guide Sent to Band Members

Nazhike — Tough Decisions Shinaabs Make

New Ordinance Modifies Child Support Code

Weekly News Summary for October 11-16

Comment period open for draft Revisor's Office statute

Separation of Powers Helps Ensure the Survival of Our Sovereign Nation

Aanjibimaadizing Moves to Former Clinic Building

Band Assembly Weekly Update, October 12-16

The Real Meaning of Community Service

Weekly News Summary for October 18-24

Detailed Gaming Regulation Revision Project

'You're Coming with Me!' — A Love Story for the Ages

Band Member Voices — Zooming Towards Recovery

Band Assembly Weekly Update, October 19-23

DNR wants your opinion on management plan

Interim Early Ed Director is Head Start Graduate

It's Time to Get Out the Native Vote!

Fall and Winter In-Person Events Canceled Due to Pandemic

One Last Reminder: Go Vote!

Public Hearing November 12 for Revisor's Office Legislation

Health and Human Services Shares COVID-19 Announcement

Band Member Voices — Raise Your Voice on November 3!

Band Member Voices — The Return of Wenabozho

Weekly News Summary, October 25-31

November 2020 Message from the Chief Executive

Reduced building access due to positive COVID-19 tests

Weekly News Summary, November 1-7

2020 Election Results: Minnesota goes for Biden; Republicans take rural districts

Band Assembly announces publication of updated laws of the Mille Lacs Band

Band Assembly Weekly Update, November 2-6

Band member named to Northland Foundation Board of Trustees

Food Distribution Friday at Grand Makwa

Native American Veterans Memorial Opens to Public on Warriors' Day

Band shifts to virtual service delivery for government, health care, education

Mille Lacs Band important phone numbers

Weekly News Summary, November 8-14

Band Assembly Weekly Update, November 9-13

Tribal Attorney Elected to City Council

A pet wellness clinic like no other

Band Assembly shares final version of Title 25 for public review

COVID surges, TERC responds

Weekly News Summary, November 15-21

Band Assembly Weekly Update, November 16-20

Self-exclusion for gambling prevention

A Hall of Fame Court Career

Band Assembly Weekly Update, November 23-27

Commissioner extends mask order until February 28

COVID-19 housing grant deadline is December 7

Richard Osburn sworn in as District Court Judge

Weekly News Summary, November 22-28

Builder wins award for Health and Human Services Building

December 2020 Message from the Chief Executive

Weekly News Summary, November 29-December 5

Native women call for Indigenous representation in Biden Administration

Band Assembly Weekly Update, November 30-December 4, 2020

Victims of Crime Program Offers Help

HAWK crosswalk installed in District I

Band member reelected to hospital board

Caravan raises awareness of domestic violence

Traditions, fitness — and ukuleles! Youth program adjusts to COVID-19

Weekly News Summary, December 6–12

Band Assembly Weekly Update, December 7-11

Housing Improvement Grants Available

Revisor's Office Bill Signed into Law

Weekly News Summary, December 13-19

Band Assembly Weekly Update, December 14-18

As vaccines arrive, COVID-19 precautions remain in place

Band continues action to stop Line 3

Telemetry study gathers groundbreaking data on walleyes

Weekly News Summary, December 20-26

Chief Executive shares lawsuit update

Band employees step up during pandemic

Legislative Branch Welcomes New Staff Attorney

Meet your Gaming Regulatory Authority Board members

Passion and dedication lead to success on the gridiron

Director brings experience to new HHS role

Sharing the Gift of Experience

CHAPS grant helps with COVID-related expenses

Letitia Mitchell — A life of hard work and plenty of laughs

Band member voices — An Anishinaabe 20/20 on 2020

January 2021 Update from the Chief Executive

Band Assembly Weekly Update: December 28, 2020-January 1, 2021

Vision Maker Media seeks public media project proposals

MLCV, Initiative Foundation seek cohort for Enterprise Academy

Six Band members graduate from Enterprise Academy

News Summary, December 27-January 8

Youth Assembly gives students a strong voice

Band Assembly weekly update, January 4-8

Project Blue Light shows support for frontline workers

2021 State of the Band Address

Reservation boundaries marked

Chief Executive Melanie Benjamin delivers 2021 State of the Band Address

News roundup, January 10-16

Band Assembly Weekly Update, January 11-15

Chief Justice provides update on Judicial Branch

Secretary-Treasurer announces publication of Band statutes

State of the Legislative Branch — Pandemic, Legislative Process, and Investments

Finding new District I buildings just got easier

Get the vaccine — for yourself, and for your elders

Tribes criticize Stauber for opposing Haaland nomination

Vaccine facts from your public health department

News Roundup, January 17-23

Front-line workers recognized with Project Blue Light

Band Assembly Weekly Update, January 19-22

Freedom from smoking course offered to Aanjibimaadizing clients

Legislative Order establishes procedures for critical nominations

Open Call for Social Change and Emerging Artist Support Programs

Participants needed for tribal tobacco study

Report shows Native Americans' perspectives on COVID-19 vaccine

Band Member Voices — An Intro to Ojibwe Language Learning

Stocking program hits new heights

Youth cooking club — Healthy, tasty, and fun!

News Roundup, January 24-30

Legislative Weekly Update, January 25-29

An emerging collage of hope

Free cement mason orientation and training

Executive Order allows restored services for Band members

Tax help available for Band members

A smiling voice on the triage line

Happy to Give — Band employee makes masks for all who need one

News Roundup, January 31-February 6

Band member voices — Giving back to the community

GRA Update — Understanding fraud

Legislative Weekly Update, February 1-5

Opwaaganag — Ceremonial Pipes

Stronghearts Native Helpline launches 24/7 operations

Chief Executive Named to federal law enforcement selection committee

Frequently Asked Questions About the Mille Lacs Reservation

Vision Maker Media celebrates 45 years

News Roundup, February 7-13

Band Assembly Weekly Update, February 8-12

State sides with Band in lawsuit against County

Niibaa-Aatisooke — Sacred Teachings in the Night Time Story

Huskies come back to beat Panthers

News Roundup, February 14-20

Tribal leaders discuss enrollments

GLIFWC tribes respond to latest Ma'iingan decision

Native communities continue to urge Congress to confirm Deb Haaland as Interior Secretary

Commissioner remembered for a life of service

March 2021 Message from the Chief Executive

Band Assembly Weekly Update, February 22-26

News Roundup, February 21-27

GLIFWC announces 2021 internships

Mask order extended until May 31

News Roundup, March 1-5

Secretary-Treasurer announces career opportunity in financial industry

Celebrate Women’s History Month with Online Films and Panel Discussion Featuring Indigenous Women Leaders

COVID-related rental assistance funds are now available

Mekweniminjig

Aanjibimaadizing, Pine Tech partnership brings new courses to districts

Band member wins competitive arts grant

Ge-Niigaanizijig Language Program

Helpline Marks Four-Year Anniversary

Sherraine White — First rung on the corporate ladder

Band Assembly Weekly Update, March 1-5

Senator says COVID-19 relief will help Tribal Nations recover from pandemic

Statement Regarding Biden’s $1.9 Trillion Rescue Plan From Chief Executive Melanie Benjamin

DNR hosts harvester meetings, raffle for Treaty Day

Notice of public comment and hearing on proposed amendments to Title 3

Secretarial Order establishes numbering system

News Roundup, March 7-13

Band Assembly Weekly Update, March 8-12

Band Member Voices — Ziigwan Energy

Curt Kalk Jr. — The right fit for HHS

Dean Reynolds — Moving up through the ranks at HHS

A Year-Long Emergency

Hypnosis event is well received

Legislative Weekly Update, March 15-19

COVID-19 Emergency Rental Assistance Is Now Available

Iskigamizige — Tradition in the Making

News Roundup, March 21-27

April 2021 Message from the Chief Executive

Band Assembly Weekly Update, March 15-19

Ellison hears boundary comments

Federal Court Hears Arguments on Status of Reservation

Notice of public comment and hearing on statute revisions

Senator Tina Smith says relief bill contains largest-ever payment to tribes

Treaty Rights Day Celebration Moves Online

U.S. sides with Band in lawsuit

Band Assembly Weekly Update, March 22-26

Ge-Niigaanizijig Fitness Club — Making Fitness Fun for Everyone

DNR hosts online meeting on spring fish harvest

Spring 2021 Harvest Guidelines for Mille Lacs

April is Child Abuse Prevention Month

TERC letter updates restrictions for indoor, outdoor gatherings

Vision Maker Media marks anniversary with environment-themed program

Grants Department is important source of funding for the Band — and the region

News Roundup, March 28-April 3

Rural emergency skills save lives

Six common tactics of sexual coercion

Attorney is first Revisor of Statutes

Band Assembly Weekly Update, March 29–April 2

Grand Casino Mille Lacs celebrates 30th Anniversary

Severe Weather Awareness Week is April 12-16

StrongHearts Native Helpline launches text advocacy

HHS shares recommendations for fully vaccinated people

Healing through culture

IPAD artist makes her mark

The Mille Lacs Band's Legislative Process

News Roundup, April 4–10

Band Assembly Weekly Update, April 5-9

News Roundup, April 11-17

Boating accident results in death of tribal community member

Get the facts about COVID-19 vaccines via online event

Tribal economy chosen for broadband program — survey participation needed

Zakab Biinjina — Supportive housing comes to all districts

Band Assembly Weekly Update, April 12-16

Broadband grant will help with internet service payments

New Indigenous-led program launches in Northeast Minnesota offering grant funding to Indigenous communities

News Roundup, April 18–24

Chief Executive releases statement on guilty verdict in trial of Derek Chauvin

Ethel Curry Scholarship now accepting applications

Casinos offer summer youth employment program

DNR conducts controlled burns

Indigenous Stories of Strength — Call for Nominations

2020 Official Acts published online

Sign up now for Ge-Niigaanizijig summer sports

Band Assembly Weekly Update, April 19-23

News Roundup, April 25-May 1

Band takes strong role in talks

EPA supports tribes on manoomin

May 2021 Message from the Chief Executive

The Right Stuff — DNR responds quickly to douse wildfire

President Biden Issues Proclamation on MMIW Awareness Day

Remember Missing and Murdered Ingienous Women on May 5

Band members need to return form to be eligible for payments

Legislative weekly update, April 26-30

Big Screen Dreams

Leaders reflect on pandemic successes and lessons

Nutrition, Fitness, Medication — Diabetes triangle of treatment

SUD Department responds to needs

News Roundup, May 2-8

Totem pole journey to DC rescheduled to begin July 14

Commissioner's Order ends mask mandate

6 Common Tactics of Teen Dating Sexual Coercion

Kegg’s Message Helped Preserve Reservation

Published

June 1st, 2017