Everyone knows everyone at Minisinaakwaang Leadership Academy in District II, and those personal relationships make education successful — not just for intellectual growth, but for emotional, spiritual, and cultural growth as well.

When Vince Merrill, who teaches Ojibwe, walks the halls, he knows them by name, students as well as staff, and he can tell you about their interests, their backgrounds, and even their moods.

"We feel like family, and that’s the way it should be," said Vince. "When somebody’s having a bad time, it's really easy for the kids to reach out."

The relationships among staff and students don't end when the bell rings, either. Vince runs into students and their families at the dance hall, the gas station, and the grocery store in Aitkin.

"When the kids see me out in the community, they mangle me with hugs," he said.

Tenth-grader Jasmine Skinaway was back in school September 13 after taking some time to go ricing with her family. Vince said those activities are allowed at Minisinaakwaang.

Vince has high praise for the staff — not just the administrators like Director Marysue Anderson or Business Manager Raina Killspotted, but the teachers and support staff as well: Dawn LaPrairie, the K-3 teacher who is in her second year; Steve Williams, the IT manager who does "a little bit of everything"; Rosa Colton, a transfer from Nay Ah Shing in District I; teacher assistants John Schmidt and Chelsy Wilkie of the Turtle Mountain Ojibwe; Kitchen Staff April Boyd, Amanda Anderson, and Mary Boyd; and Elders Marene Hedstrom, Laura Shingobe, and Winnie LaPrairie, who share time so there's always an Elder present.

"They command a lot of respect," Vince said. "And they have a great sense of humor."

Learning by doing

The Elders are also resources in Minisinaakwaang's most im- portant asset: cultural knowledge.

The curriculum at the school includes local and national tribal history and seasonal cultural knowledge.

Although this year's poor rice crop has limited the school's trips to the lake, students are normally exposed to ricing in the fall, storytelling in the winter, sugarbush in the spring, and Ojibwe arts and crafts year-round. This winter each student will learn an Ojibwe story, and they will bring those stories to the community in a public performance.

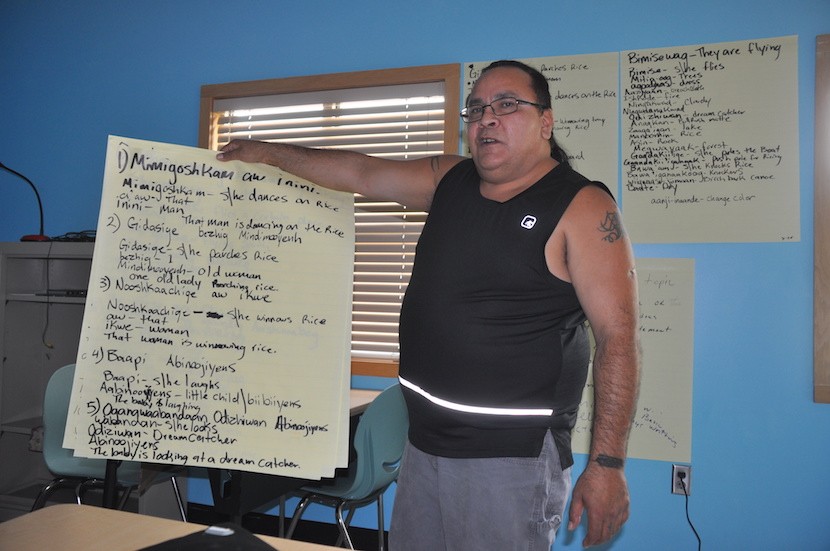

Language instruction is one of the strengths of the program, thanks to Vince and his apprentices: Branden "Husky" Sargent and Tony "Wug" Killspotted.

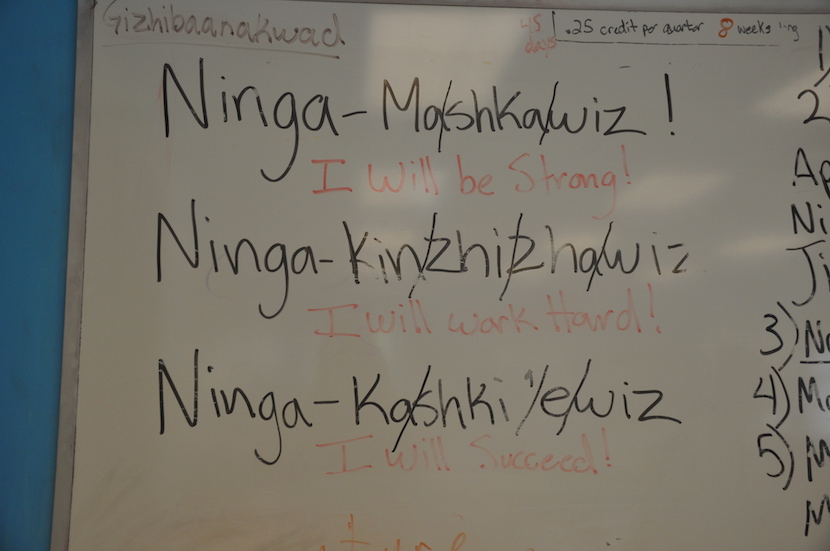

The importance of language is evident all over the walls in the high school classroom. Ojibwe words and sentences and labeled pictures adorn every empty space.

Some of that is by design, some by necessity. The projector went out, and they haven't been able to get a new one, so Vince is using old-fashioned methods: handwritten lessons on big sheets of paper.

"We’ve been using the same technology since the place opened," Vince said. "We have to make do with the things we have. We do it, but it would be nice to one day have comput- ers set up for the kids and show them more visual language through computers."

Aiming high

Despite the challenges, however, the school maintains high standards and a focus on learning.

"We always set the standard high because we want the kids to walk away successful," said Vince.

Minisinaakwaang's efforts are paying off. A lot of the students are "math whizzes," according to Vince.

One seventh grader is already learning algebra — a subject that isn't offered until much later in public school.

Another is reading at a 10th-grade level, thanks in part to the new accelerated reading program. Many of the students are great readers, which comes from giving them a choice of relevant literature.

High school students have read Anton Treuer's The Assassination of Hole-in-the-Day, and Kent Nerburn's Neither Wolf Nor Dog.

"We took them to see the movie after they read the book, and they said the book was better," said Vince. "When you have kids saying that, you know you're doing something right."

Molly Bohanon, a Minisinaakwaang senior, was recently honored with an invitation to participate in the Dartmouth Bound Native American Community Visitation Program October 7–10. The all-expenses-paid visit to Dartmouth College — an Ivy League school in New Hampshire with a renowned Native American Studies program — includes assistance with the application process and financial aid.

Vince gets especially proud when he talks about Daisy Taylor, a graduate from last year who happens to be his we'eh.

Like many teenagers, Daisy was struggling in ninth and tenth grade.

"Something just clicked one day, and she became an awe- some student and a role model for others," said Vince. "All of a sudden she grew up, started following the rules, went to class every day, and took the opportunity to study when kids were playing in the gym. The last year it was remarkable to watch her blossom, and it was such an honor to watch her smile and get her diploma."

That kind of success comes through a combination of high standards, a supportive atmosphere, and meaningful curriculum based in the culture.

"This is beneficial to these kids because they need to know where they come from," said Vince. "Seasonal activities were not just a way of life, but an instrument of education. They teach kids that once you start a job, you have to finish it. You have to follow that process through to the end."

Thanks to schools like Minisinaakwaang, those cultural activities and the language to describe them will continue to survive and thrive.

The warm environment of Minisinaakwaang Leadership Academy makes every student feel special, but they are also held to a high standard by Ojibwe teacher Vince Merrill, top, and the rest of the staff.