The 1837 Treaty case was filed in 1990 and finally resolved 20 years ago on March 24, 1999, with a Supreme Court decision affirming the Band’s right to hunt, fish, and gather in the territory ceded to the U.S. government by the Ojibwe in 1837.

But the case really began well before 1990, with a series of arrests and citations of Band members by state conservation officers.

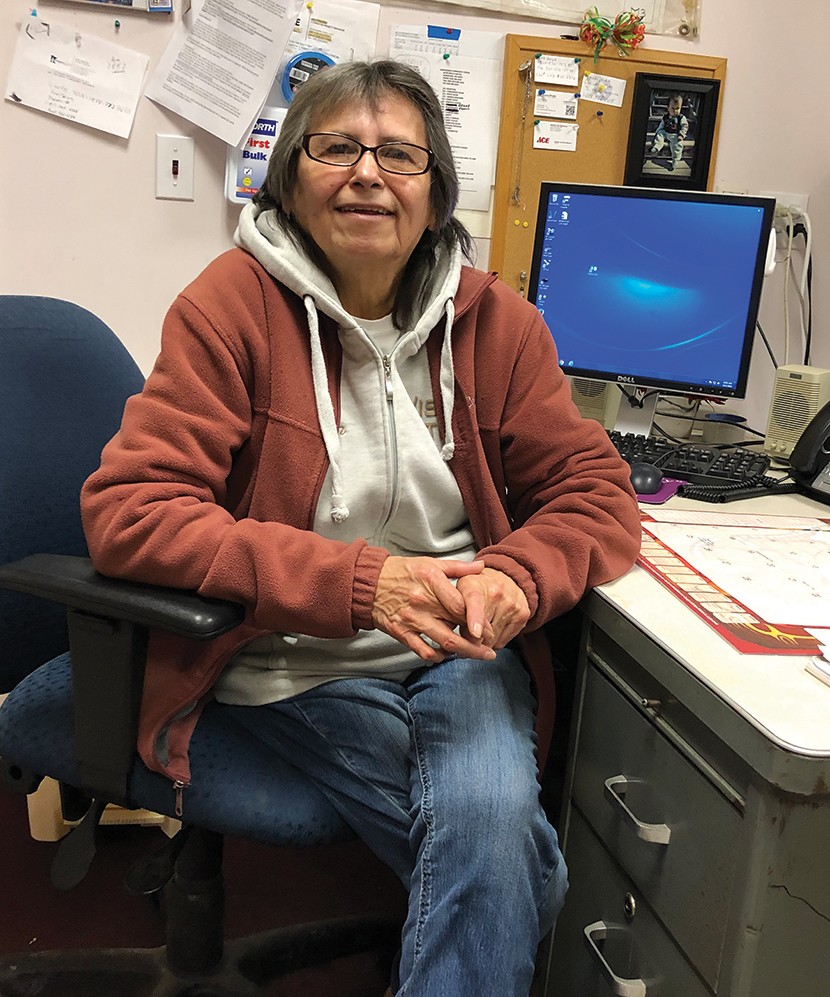

Carleen Benjamin was one of the plaintiffs named in the lawsuit after she was ticketed for ricing without a license.

She doesn’t remember the date, or even the year, but she does remember what happened.

Carleen wasn’t planning to go ricing that day, but her kids’ dad, Virgil Skinaway, broke his foot and couldn’t go. His friend Pat Reynolds needed a partner, so she agreed. “I don’t even really like water,“ Carleen joked.

Carleen was never an avid ricer, but she went out on Crooked Creek and Hay Creek as a child. She also recalls going up to Moose Lake to rice with her brother, and going out with Virgil from time to time.

Her mom, Nina, and her dad, Jim, told her they didn’t need a license to fish, hunt, or harvest rice.

Pat poled and Carleen knocked, and when they got to the landing at Crooked Creek with a sack and a half of rice, a state conservation officer was waiting. He took their rice and gave them a ticket, which Carleen paid in Pine City.

Although she didn’t testify at the federal trial, she was interviewed by attorneys about her experience that day. “I got a letter in the mail asking if I would go down to St. Paul because they were trying to get the treaty rights recognized,“ said Carleen.

For the last 19 years, Carleen has been the maintenance supervisor at Aazhoomog Clinic, a short walk from home. Nowadays she enjoys work and spending time with her kids and grandkids — with an occasional trip to the casino.

Although she doesn’t think much these days about her role in the treaty case, she’s proud that she was part of it. “I’m just glad that the Band got what they wanted out of the situation,“ she said.

According to the Band’s attorney, Marc Slonim, the individual plaintiffs were selected because they had been cited for violating Minnesota natural resources laws while engaged in traditional, treaty-protected harvesting activities.

“We were looking for Band members who had been harmed by the State’s enforcement of its natural resources law,“ said Marc.

The other plaintiffs — Arthur Gahbow, Joseph Dunkley, and Walter Sutton — have passed on, but their names will forever be associated with the case and the Band’s victory.

According to long-time Band employee Don Wedll, Chief Executive Art Gahbow had been cited for spearing a sucker. The fish and spear were confiscated, and the commissioner of the Minnesota DNR, Joe Alexander, had the fish and spear head mounted and gave it to Art as a gift.

Joseph Dunkley was cited for fishing with multiple lines, something he said was a common practice in the Aazhoomog community. He was an avid hunter and fisherman who testified in the 1837 Treaty case.

They were only a few of the many Band members whose rights were violated by the state over the decades. Another member, Herman Kegg, testified during the trial that he had served 60 days in jail for violating state regulations.

They didn’t do it as a protest or in preparation for a court case, but simply to practice and preserve traditions that had been passed down for generations.

That holds true for Carleen, whose simple act of helping a friend landed her in the history books — and cost her a sack and a half of rice.