By Brett Larson, August 4, 2015

Luther Sam’s story shows there’s hope after heroin

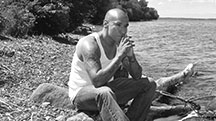

Every morning, Luther Sam crosses the highway to the shore of Mille Lacs, where he puts out tobacco and says thanks for the gifts he’s been given. He prays for the people he’s hurt, and he asks for help to make it through another day.

Luther’s story is a warning to anyone who thinks drugs are a game, but it’s a beacon of hope to those caught in the powerful grip of heroin or other drugs.

Like many addicts, Luther was drinking by the age of 14. “Right from the jump I was experiencing blackouts,” he recalls. “I’d wake up in a juvenile detention center not remembering how I got there. It was like my brain just turned off. Booze and drugs take over. And what’s crazy is, you do it again the next day.”

He’d lose hours on those binges. He would get in fights and wake up with bloody knuckles and bruises on his face. He spent his adolescence accumulating a record of minor consumptions, drunk driving and assault.

When Luther turned 18, things got worse. “I started using meth in a big way,” he says. “Back then, people on the reservation were kind of sketchy about people who used meth. But then it blew up.”

For the next 10 years, it was more booze, more drugs, more blackouts and more arrests. He started using Percocet, Vicodin and Oxycontin. “I’d be up for days, experiencing hallucinations. I spent time in jails, hospitals, detox centers, prisons. I slept on every state bed there is,” Luther says.

In 2008, Luther was sent to prison for the first time for 3rd degree assault. Prison wasn’t difficult for Luther because he had spent so much time in detention centers, county jails and treatment centers. He was comfortable with the routine, and he had developed a “survival instinct.”

When he got out in 2010, he tried to get his act together. He had a daughter and a job to keep him focused. One day he was complaining to a girlfriend that he didn’t want to go to work. She offered him heroin, and he accepted.

“Heroin was the lowest point for me,” he says. “It became my life from the first try — a 24-hour kind of thing. Looking for it, getting it, using it, wanting it, and the cycle would start again the next day.”

He started out sniffing it, but during the last year of his addiction, in 2012 and 2013, he was using IVs, often mixing heroin with methamphetamine.

Luther knew he was in trouble, so he checked into a treatment center where he was given Suboxone, Gabapentin and Klonopin, allegedly to help him get off heroin. “I walked in with a heroin addiction and walked out with a barbiturate addiction. As soon as my prescriptions ran out, it was right back to heroin and meth. Right where I left off. Nothing changed.”

Luther went to prison again on April 26, 2013, which marked his first day of sobriety. Although drugs were available, Luther stayed clean, and one night he knew he wouldn’t be going back to his old ways.

“There was a big riot in prison, and I got some segregation time. While I was there, something happened in the middle of the night.” He asked himself what was causing his addiction, the real reason for his troubled past.

“I knew I was lost,” he says. “I had no sense of who I was, no sense of purpose. I needed spirituality in my life.”

Luther calls it a “spiritual awakening.”

“I started to pray every morning, quietly to myself. ‘Give me the strength to make it through today. Watch over my daughter. Watch over my grandma. Watch over my mom. Thank you.’ Every day. It just felt right. It felt like this is who I am, and this is what we need to do as Anishinaabe people.”

Luther experienced an intellectual awakening, too. He turned off his TV and started reading books. At the prison library he checked out The Red Road to Wellbriety, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, and Custer Died for Your Sins. He started writing letters to friends in other jails.

Since his release from prison in February, things have steadily gotten better for Luther. He’s received help from his friends Pat McCoy and Richard Hill, the manager of Mino Bimaadiziwin (“Mino B”), the old Budget Host Hotel where Luther was paroled. He has a full-time job and a driver’s license. He’s paid off his fines and restitution.

Meetings and ceremonies, especially the sweat lodge, help Luther stay clean and sober. He’s hosting a wellbriety support group at the Mino B on Saturdays at 6:30 p.m. — to help others as well as himself.

He also credits his grandmother, Dorothy Sam, for planting the seeds of recovery.

“My grandma was always talking about offering tobacco,” Luther says. “If you’re looking for answers, go to the Creator, ask the Creator and offer tobacco. Things she used to tell me didn’t make sense back then, but it all makes sense right now.”

Recovery is not without its struggles. Luther has ended relationships and faced hard facts about himself — including violence committed against his former partner. “There’s nothing I could do or say that could make up for what I did to her — getting drunk and hitting her,” he says. “I was a really bad person.”

He’s had to forgive himself and focus on the present day, trying to learn something new, to experience something positive. “Today I’m proud,” Luther says. “I’m appreciative of who I’ve become. I’m doing things to better my life so my daughter can have a better life. I want her to have a strong, positive, cultural role model.”

Luther wants other addicts to know there’s hope. “In recovery, anything is possible,” he says. “It doesn’t matter how far you’ve gone into drugs. There’s hope that you can overcome. Don’t set limitations. Trust that the Creator has absolutely unconditional love for you. Everything we have in life is a gift, and it needs to be appreciated and respected as a gift — our kids, our partners, our home, our job.

“Three and a half years ago, I thought there’s no way I’m gonna get off the drugs. I thought the only way out would be death, but here I am today, happy as ever. If I can do it, anyone can.”