When my son, Dallas, was three years old, he told me he wanted to dance at the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe’s Traditional Powwow. When I asked him why, he said it was because he could feel the beat of the drum in his heart. The following year, as soon as we arrived, he ran into the circle and began to dance.

There were many other reasons that Dallas, now 10 years old, wanted to dance and why he continues to dance at powwows today, but it was the sound of the drum that beckoned him.

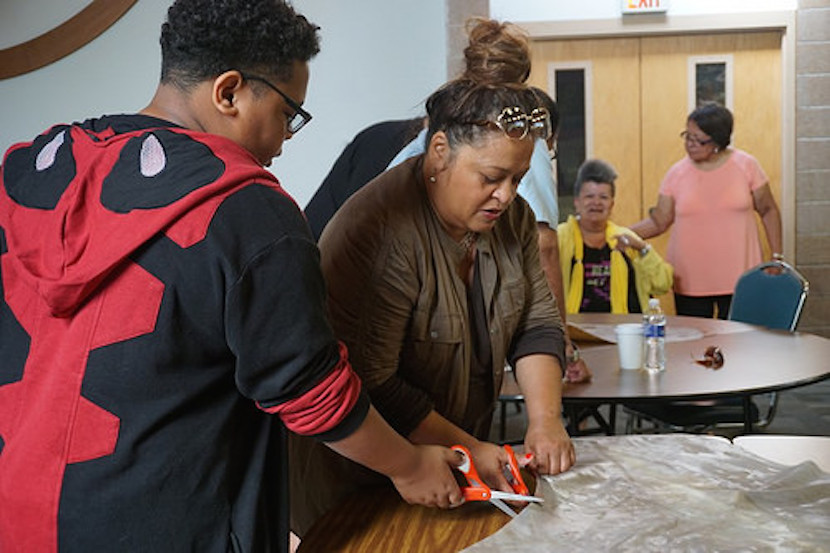

Recently, when the opportunity to make a hand drum was offered through the Band’s urban office, Dallas jumped at it. So did 20 others who quickly filled the roster for the day-long class that was held in early August at the All Nations Church in Minneapolis.

The class was taught by Band member Terry Kemper and Laurie Vilas. Terry works in the Band’s Historic Preservation Office, and Laurie works as a peacekeeper for the Band’s Tribal Courts.

A drum is “the heartbeat of the mother,” said Terry as he explained a creation story before we began making the drums.

He told us that when people are born the process is scary as people move from the spirit to a human form. “But the one thing we can rely on is our mother’s heartbeat,” Terry said. “It continually beats to us. The vibration is in the water the babies grow in.”

“Then, for many, the older they get, the farther from the vibrations of life, the vibrations of the trees, the wind, and the vibration of animals people tend to get.”

“However, the vibration of our mother’s heartbeat is everywhere, and it’s sustained us as Anishinaabe people,” he continued.

Terry continued to explain the history of drums, what they were used for and how they were made. Co-presenter Laurie provided other details as well as gifted all of us with branches from trees that were already peeled and smooth so we could make them into drumsticks.

The 16-inch hoops we used to make our drums came from maple trees. We also used buffalo hide, some of which was dyed in various colors, to complete our drums. As we worked on our drums, Terry reminded us of the connection to the Earth through its gift of the buffalo and maple trees.

My nephew, Blake Ford, 15, said the experience gave him “a whole new level of respect for the people who make drums because it was very involved and it took a lot of work.”

He added that he looks forward to using it one day soon.

Throughout the day, which was filled with teachings, laughter and a sense of community, our group helped each other as much as possible. Whether it was cutting laces to wrap the drum, assisting with tools, helping Elders and youth or cleaning up the tiny pieces of buffalo hide from the church’s floor, a spirit of sharing filled the space.

During the day Terry and Laurie talked about the songs that were sung with the drum, and they taught our class how to sing songs as we were working.

One participant, Alexander Skinaway, who is 20 and came with his grandma, said it was his first time making a drum. He called it a great experience.

Seventeen-year-old Dakota Skinaway thought it was “pretty cool.” “I’ve never made a drum before, and it’s a

learning experience,” said Dakota.

My sister, Tawnya Stewart, who is also a Band member, said the teachings of Laurie and Terry were greatly appreciated because of their unending patience, their dedicated assistance and their desire to teach all of us about the significance of what we were doing.

“I want to give a special thanks to Laurie and Terry for being such great instructors,” said Tawnya. “They worked to help ev- eryone walk away with a beautiful drum.”

Before we left for the day, Terry and Laurie instructed us to take our drums and hang them up for four days — out of the sun — so they didn’t dry out too fast. And so they didn’t wrinkle. They told us we could paint them and gave us instructions on how to do that.

Four days after our class, when our drums were dry, my husband took his drumstick and we listened to the sounds from both drums we made. Those sounds, while different in pitch, made our hearts race a little faster. And whether Dallas realized it or not, the sound of the drum continued to connect him to my heartbeat and that of our Anishinaabe culture.